Lifestyle

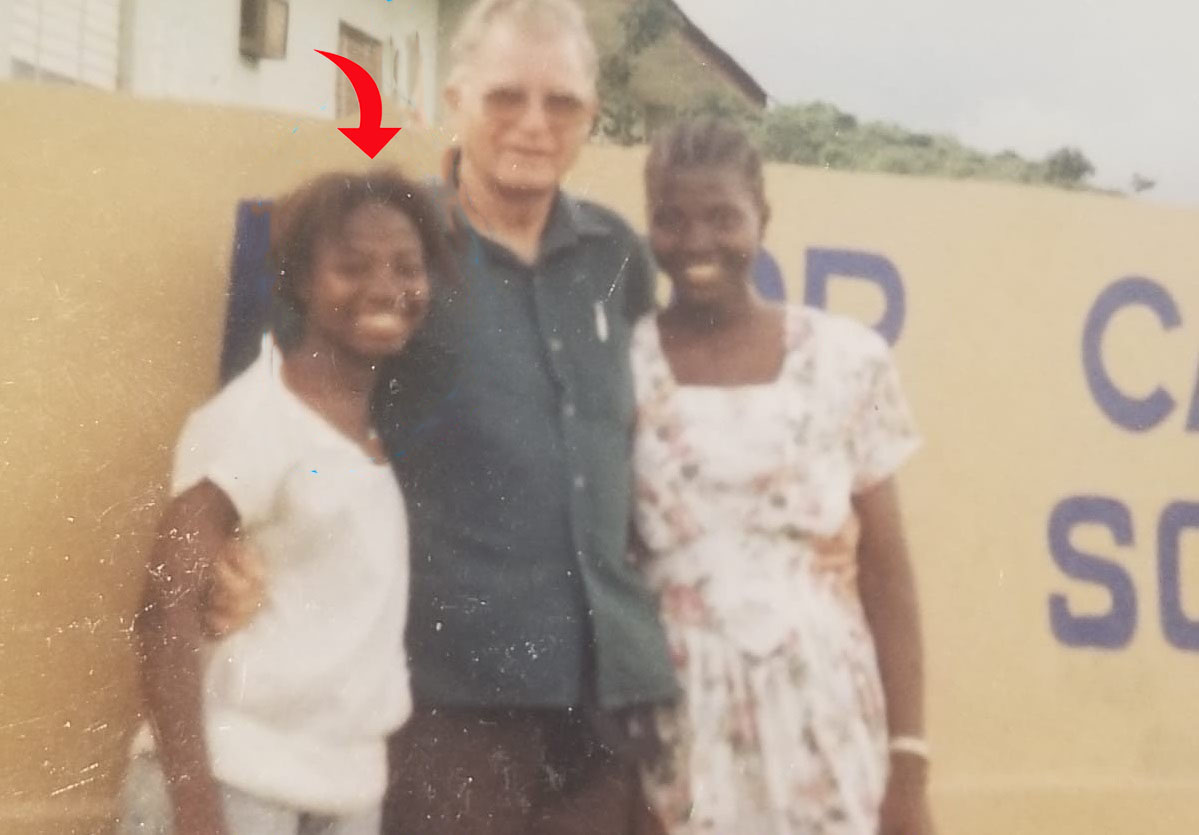

Dr Paye-McCain: The Scientist, War Survivor Who Spent 10yrs To Complete First Degree.

Published

3 years agoon

By

Joe Pee

Many women have had their dreams truncated due to societal barriers induced by culture, religion, gender, war and poverty, but some remarkable personalities have defied such odds to rise to the top.

For some, these adversities have become stepping stones for success in contributing to shaping society for the better.

One of such remarkable achievers is Dr Plensey Diana Paye-McClain, an Assistant Professor and Chair, Department of Medicinal/Pharmaceutical Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, University of Liberia, Liberia.

Despite devastating wars in her country, which resulted in over 200,000 deaths, displacement of more than 750,000 civilians, and many Liberians becoming refugees in neighbouring West African countries, Dr Paye-McCain survived and rose to the top as one of few female scientists in the tiny West African country along the Atlantic coast.

She fled Liberia as a teen and lived under difficult conditions of extreme hunger in Cote d’Ivoire for more than ten years until the bloody conflicts ended.

It takes six years for undergraduate and master’s programmes, but the determined woman spent 16 years to complete the courses.

Her relentless spirit was a catalyst to push her beyond the line.

She is one of six scientists recognised by the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), UK, through its inclusion and diversity activities and widely acknowledged on the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

The mother-of-two is acknowledged as one of the few top female West African scientists serving as role models to the younger generation.

Dr Paye-McClain shared her story to drive change and challenge societal barriers against women within the chemical sciences.

We bring you the captivating journey of Dr Paye-McClain’s professional experiences, successes and obstacles and how conflicts, war and the Ebola crisis impacted her trajectory.

Q: What inspired you to choose a career in science?

Dr Paye-McClain: I grew up on a Firestone rubber plantation with my parents in Liberia. My childhood was not easy, and I had to walk two hours to school and two hours back home each day.

During those periods, I will see latex draining from rubber trees and sometimes, you will see a sheet of caked rubber.

Then I wonder how a liquid could transform into a sheet of solid caked rubber.

Those were the things that I wondered about continuously and wanted answers to.

I started to have many questions…and wanted to know more. That is how my interest in science began.

For a while, I also lived with my uncle, a medical doctor, and I had the opportunity to ask many questions about medicine and science.

As a Pharmacist, I know that science is evolving, and drugs for some diseases have changed because of science.

I didn’t have the opportunity to be in a laboratory in my elementary and high school because there were no laboratories.

Still, I was inspired because I always made good grades, and my teachers made me understand that science was life.

Q: Tell us about your journey, the impact of the wars and becoming a scientist.

Dr Paye-McClain: Like the Nigerians would say, “It’s a long story, but I will cut it short”.

When my father and my mother separated, my sister and I grew up whiles staying with my father a little bit in a Firestone rubber plantation, where we tapped rubber.

Later, I went to stay with my uncle who was working with a mining company, and I lived at the staff quarters.

I sat home, and a school bus would come and take me to school, and that was exciting. I had never seen that life, so it was exciting for me. During all those times, science was on my mind, and I made good grades in all the schools I attended.

But that changed drastically.

My uncle had to leave Liberia for further studies in the United Kingdom (UK). So, I had to return to live with my mother.

I wrote an entrance examination to a school with a laboratory.

Guess what? Boom! The Liberian Civil War.

It started on 24 December 1989. So it was just on Christmas Eve, and I was 11 by then. I was going to Junior High School, what we call 7th Grade in Liberia, but all this ended abruptly.

My dreams for a career in science seemed to fade away when civil unrest was at its peak in Liberia – there was death and hunger all around me.

My parents moved me quickly to Cote d’Ivoire to stay with an aunt.

I lost four years of education. At that time, I was about 15 to 16 years old.

My mother was a pillar of support and believed in education, but funds were low. However, my mother persevered and worked hard in the market selling fish and saving money for my school fees.

Q: How was life in Cote d’Ivoire?

Dr Paye-McClain: I lived in a refugee camp, so there were no laboratories. Sanitation and hygiene were poor, and there were no lavatories as well.

But I survived.

I graduated from Senior High School (SHS) with the best grades in the sciences and top of my class.

It was good news for me.

Just around the time, the 14-year civil war had ended in Liberia, and there was an election.

I moved back to Monrovia and enrolled at the University of Liberia at the Fendall Campus in Louisiana. I wanted to do Pharmacy, so my first choice was B.Sc Chemistry.

Remember, it takes four years for an undergraduate programme, but I spent 10 years.

The four years turned into 10 years due to a shortage of instructors.

Additionally, there were pockets of unrest, so sometimes, we had just one semester within a year instead of three semesters.

Through this, however, I built resilience and perseverance. I obtained my Bachelor’s degree in Pharmacy at the University of Liberia.

Someone asked me: “After 10 years are you going to do Pharmacy’? I laughed and said, ‘Yes, I am determined’”.

And so, I enrolled at the School of Pharmacy. Again, it should have been four years, but it took me six years because of the same lack of instructors and funding at the university.

Later, I obtained my Master of Science in Pharmaceutical Chemistry in 2016 from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria and my Doctorate in Pharmacy in 2019 from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Benin, Benin State, Nigeria.

Q: What are some of the barriers along your journey?

Dr Paye-McClain: My family has been my support.

I would say back in school, the boys didn’t understand why I wanted to do science.

“You, a girl, you want to do science and measure arm with the boys,” they would say.

I didn’t see it as a barrier but motivation for me to forge ahead.

During my undergraduate days in a differential calculus course class, I was the only female student with approximately 50 male students. Nevertheless, I saw this as a platform to raise my voice and be heard.

When I was at the School of Pharmacy in my second year, my husband travelled to do his master’s, which was tough.

My mother stood by me and took care of my first baby while I attended school.

In fact, she had been of great help, and I am so grateful to her.

Q: A career in science takes up a lot of time. How do you juggle family life with your work and other commitments?

Dr Paye-McClain: Mothers always find available time…. My husband has a nickname for me – manager! I have found that having a to-do list helps as I juggle cooking, preparing lecture notes, nurturing my daughters, who are 11 and 8 years old…My mother also helped take care of my first daughter when I was completing my training at the School of Pharmacy.

Q : Who were your role models growing up?

Dr Paye-McClain: I have been lucky and blessed in this regard. Firstly, the family support I have had throughout my childhood and education has been phenomenal. I was taught and grew up with Christian beliefs that have helped me face turbulent times in the midst of conflict and war. Many a time, I said a prayer of hope at the refugee camp.

Secondly, the Dean of the School of Pharmacy where I studied was a mentor who gave me the opportunity of working as a teaching assistant as I worked towards my Masters in Pharmaceutical Chemistry. Unfortunately, he died in January 2021, and I feel the loss acutely.

I will always remember a phrase from him: “You should do everything possible to measure up to the boys”.

Everyone should have a mentor.

Q: Tell us a bit about your current work?

Dr Paye-McClain: Currently, I am the Departmental Chair at the Department of Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry. My work entails lecturing, preparing schedules, monitoring instructors and students, representing the faculty at senate meetings and guiding and supervising students undertaking research. In 2021, we were very busy in the School of Pharmacy with the production of W.H.O recommended alcohol-based hand sanitisers to be used as part of COVID 19 protocol measures nationwide.

In 2015, I was involved in the Ebola Vaccines Clinical Trail, where I supervised other pharmacists in filling and tagging syringes containing vaccines. It was difficult but rewarding.

Q: Has the Ebola crisis and other conflicts impacted the choice of science or career progression in the sciences for girls?

Dr Paye-McClain: The Ebola crisis has had negative impacts. For example, the University of Liberia is currently focused on its public health program, i.e. biology, with little attention paid to chemistry and physics. The COVID-19 pandemic has made this worse.

In the current undergraduate B.Sc Chemistry course, the ratio of males to females is approximately 10:1.

Science is not a popular subject of choice for girls in Liberia. The reasons are multi-faceted. Gender-sensitive processes are not practised.

Q: How can we get more girls to study science and your advice to make this a reality?

Dr Paye-McClain: We must start from the elementary levels and focus on the family set-up where mothers encourage their daughters and lead by example.

We really need to change the narrative around women in science. We need to be visible – photos of scientists in lecture rooms, we need to advocate to lessen the barriers that make it more difficult for girls to take up chemistry courses.

There are societal and cultural barriers, but we should not be relegated to kitchens and caring for homes.

Q: What would be an excellent approach to scale up the number of girls pursuing higher education in science?

Dr Paye-McClain: We have to encourage them right from the elementary level. I didn’t know I was making a mark on my second daughter until she told me one day.

Every time I got home, she would be running after her sister, who would be on a bicycle.

She was so afraid she didn’t want to ride.

So, one day I called her and told her she could make it and told her to repeat the words, “I can make it”.

After a week, she told me, “Mummy, I am about to show you something”. She got on a bicycle and started to ride, and I began to clap and hug her.

After two days, she told me she started to ride well because I told her she could make it.

The little words we say to our students impact them. The photos our students see stay in their minds, and we must work on the minds of young girls to let them know that they can make it.

Mentorship will be one of the best things. Without a mentor, no one can make it.

Q: What would be your advice to young girls, especially those who aspire to be scientists?

Dr Paye-McClain: My pastor uses P-U-S-H as an acronym; P-Pray, U-Until, S-Something, H-Happens, but I have changed it, and I say – P-Push, U-Until, S-Something, H-Happens.

Be determined and tell yourself, “I can make it”.

The brain that God has given them is enough to achieve whatever they want. Nothing can stop them from making it.

You may like

-

VIDEO: Kofi Kinaata Hilariously Reflects on His Childhood Dream of Becoming Ghana’s President

-

Woman Seeks Advice After 8-Year Relationship Ends with Fiancé Marrying Another Lady

-

GFA Dissolves Black Stars Management Committee After AFCON Qualifying Failure

-

Ukraine to Launch Ready-to-Eat School Meals Initiative in Ghana and Other African Nations

-

NDC Applauds IGP’s Firearm Ban and Security Protocols for 2024 Elections

-

Riding Toward Victory: Konlaabig Rasheed Bolsters NPP’s Grassroots Campaign with Strategic Donation

-

Woman Dies of Kidney Failure After Husband Allegedly Misuses Donations Meant for Treatment

-

House Help Granted Bail in Alleged Acid Attack Case After Two-Year Investigation

-

Wedding Called Off as Couple Discovers Genotype Incompatibility