When the pandemic hit, the pace of research only accelerated, with researchers communicating from dingy basements on the communication platform Slack and over Zoom calls.

“2020 was a crazy year for many reasons. It gave us something to focus on,” Phillippy said.

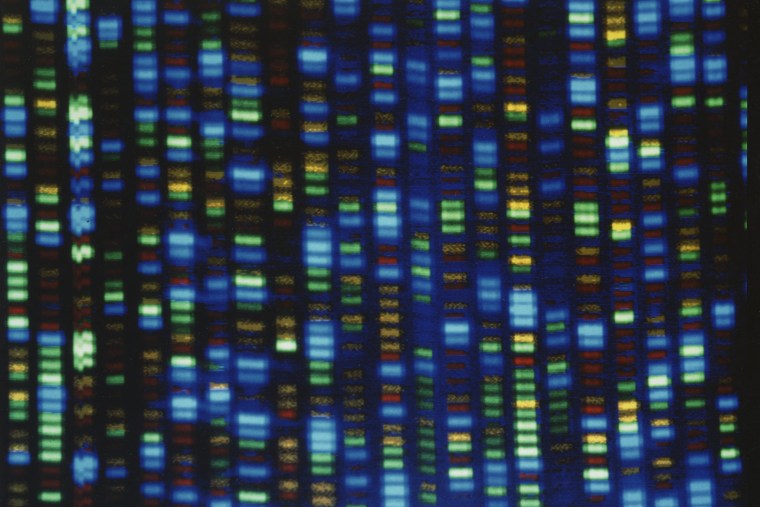

Ultimately, the researchers pieced together the entire genetic code for a single version of a genome. That genome — which was derived decades ago from cell tissue that contains the genetic information of a single sperm — does not represent any human who ever lived because it only contains one set of paternal chromosomes.

The completed code will now form the backbone of new genomic research, and becomes a new, finished reference for comparison.

Theory and practice

The completed genome opens new avenues for research.

For decades, scientists have been poring over the 92 percent of the genome available, probing it to find genetic variations that could be causing diseases.

“We have a good grasp of what variation looks like in those regions, but we have no idea about the other 8 percent,” Phillippy said.

Now, researchers are reanalyzing their old data against the new reference genome, trying to tease out new clues from what had been missing.

“We identified many more, tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of new variants,” Dennis said. “Some of them fall within genes that encode proteins and some of those genes are medically important, clinically important, and contribute to diseases.”

The new genome reference also enables further study of how centromeres work.

Centromeres are structures in the middle of chromosomes that are filled with repeating sequences of code and integral to the cell division process. They’re historically among the least understood parts of the genome because they contain so much tedious, dense coding.

“We don’t understand the underlying mechanism of the evolution of centromeres,” Henikoff said. “All of a sudden in the past year as the data have been coming out, we’ve been learning a lot more about centromeres.”

Using the new genome, researchers can better study how centromere proteins assemble and what happens when they change or lose function.

“Centromere dysfunction can be a serious driver in cancer,” Henikoff said. Until now, “we’ve been hampered because we haven’t had a reference sequence.”

Further study of newly-sequenced portions of the genome could also help scientists better understand how humans evolved particular traits, such as the bigger brains that sent them down a genetically distinct path from their great ape ancestors.

“The things that make our frontal cortex bigger come from the genes that map in these repetitive regions,” said Evan Eichler, a professor in the department of genome sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine and also part of the research collaborative.

Advances in genomic sequencing technology could drive a renaissance of medical breakthroughs, the researchers say.

“I’m more excited about what we don’t know and the opportunities for discovery,” Miga said.

Phillippy said his next goal is to streamline the sequencing process to make it cheaper, more efficient and broadly available. He also plans to sequence genetic code with both paternal and maternal chromosomes. Sequencing broadly among people from many backgrounds will help describe the world’s genetic diversity and home in on important genetic variations, he said.

He envisions a world in which everyone has access to their genetic data, which could help provide individualized information about what diseases doctors should watch for or which drugs to prescribe.

“Within 10 years, getting a complete, perfectly accurate human genome will be a routine part of health care and it will be cheap enough that it won’t be a second thought — an under $1,000 lab test,” Phillippy said. “You’ll have the complete genome in your pocket.”