International

How the recoil from Russian gas is scrambling world markets.

Published

3 years agoon

By

Joe Pee

Just months ago, Germany’s plans to build a terminal for receiving shiploads of liquefied natural gas were in disarray. Would-be developers were not convinced that customers would make enough use of a facility that can cost billions of dollars. And concerns about climate change undermined the future of a fossil fuel like natural gas.

Perceptions have changed. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Kremlin’s threats to sever fuel supplies, the government in Berlin has decided it needs these massive facilities — as many as four of them — to wean the country off Russian gas and act as a lifeline in case Moscow turns off the taps. The cost to the taxpayer now seems to be a secondary consideration.

Most of the gas that Europe buys from Russia to power its electrical utilities is delivered through pipelines, over land or under the sea. Liquefied natural gas provides another way to move gas great distances when pipelines are not an option. Natural gas is chilled to a liquid and loaded on special tankers. It then can be transported to any port with equipment to turn it back into a gas and pump it into the power grid.

“We are aiming to build LNG terminals in Germany,” Robert Habeck, the country’s economy minister, recently said before talks with potential gas suppliers.

Habeck is a politician from the environmentalist Greens but is finding, somewhat to his dismay, that Germany needs the fossil fuel.

On Saturday, Lithuania said it had stopped buying natural gas from Russia. The cutoff won’t cause much pain to the Russian budget because Lithuania is a tiny country. But, as a member of the European Union, its decision held symbolic geopolitical importance. Europe’s energy transition took on new urgency Monday in the wake of global horror at images of bodies lying in the streets in areas of Ukraine from which Russian troops have withdrawn. Leaders debated how to punish Russia without putting Europe at risk of losing critical fuel supplies too quickly.

Much as it is changing attitudes across Europe and in Germany, the continent’s largest economy, Russia’s invasion into Ukraine is reshaping energy markets globally. For years, Europe has imported enormous volumes of gas from Russia to heat homes and power industry, but now that practice, which depends on billions of dollars’ worth of pipelines, faces severe curtailment.

The EU wants to end what is now deemed an unhealthy entanglement by 2030. Within a year, it wants to slash dependence on Russia, which supplied 40% of European gas last year, by two-thirds.

How will these huge volumes of Russian gas be replaced? The EU is betting on liquefied natural gas.

Europe’s leaders want to round up 50 billion cubic meters of additional LNG cargoes over the next year, which amounts to about half of the Russian gas it wants to ditch. That’s not all Europe is doing. Officials could get more gas via a pipeline from Norway and Azerbaijan. They also want to reduce gas consumption by ramping up wind and solar power projects, and are calling on citizens to turn down thermostats. But analysts say that Europe would struggle to swiftly replace so much gas. That is one reason that Germany is preparing for rationing.

These higher volumes of LNG, which would most likely need to continue for years, could cost around $50 billion at current prices, but much less if bought on long-term contracts from the United States, where prices are a fraction of those in Europe and Asia.

Europe’s scramble raises the prospect of a global battle over supplies in a market that analysts say has little slack. Asia, not Europe, is usually the prime destination for LNG. China, Japan and South Korea were the leading buyers last year.

The additional gas that Europe is targeting would add around 10% to global demand, creating a tug of war with other countries for fuel. That prospect could mean that gas prices that have touched record levels in recent months will remain high, prolonging misery for consumers and squeezing industry.

On Friday, for instance, home energy bills for millions of British consumers rose by 54%, largely because of soaring wholesale gas costs. Futures prices don’t offer any sign of relief.

“Over the next three years, competition for LNG is going to be extremely fierce,” said Massimo Di Odoardo, vice president for gas at Wood Mackenzie, a market research firm. “Europe and Asia are going to be pulling the blanket” to cover their needs, he added.

In theory, high prices should spur investment in more gas fields. But it is far from certain how much new production today’s high prices in Europe will encourage.

“Clearly in the short term you can’t replace that amount of gas,” said James Henderson, chair of the gas program at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, a research institution.

But, Henderson added, Europe is also likely to spend money accelerating its shift to cleaner energy, reducing demand for fossil fuels.

That potential damper isn’t stopping Germany from building what would be its first liquefied natural gas terminal and a flurry of new and expansion projects elsewhere in Europe. Berlin seems to have settled on a permanent terminal for a port called Brunsbüttel near Hamburg and also has options on three floating structures, which are cheaper. One could be ready in a matter of months.

Even before the latest announcements, LNG volumes for Europe were outpacing Russian pipeline gas. Tankers carrying gas were attracted by the high prices in Europe, which were stoked by tensions over Ukraine; they are now about seven times what they were a year ago. Those prices are a boon to the world’s major liquefied natural gas exporters: Qatar, Australia and, above all, the United States, whose shipments of the fuel, a product of shale drilling, increased by 50% in 2021 over the year before.

These energy riches bring political clout. Washington has been offering LNG to help Europe break its Russian energy links, a longstanding goal of some U.S. politicians.

On March 25, the Biden administration and the EU agreed that the United States would “strive to ensure” that at least 15 billion cubic meters in additional LNG this year reaches Europe, an amount comparable to around 10% of the gas that Europe imports from Russia.

Analysts say that this commitment is achievable, but mainly because of market dynamics rather than government policies. In the first three months of 2022, at least 115 cargoes of chilled gas left the facilities of Cheniere Energy, the largest U.S. supplier of LNG, and headed to Europe, more than double the total in the same period in 2021, according to the company.

Di Odoardo figures that LNG flows from the United States to Europe have already reached two-thirds of the bilateral target for this year, and so reaching it should be “easy.”

Washington has also leaned on other countries, including Japan, to give up some of their cargoes, and this has led to a substantial drop in shipments heading to Asia from the United States, according to analysts. Over time, though, such generosity may be a harder sell, especially if the war in Ukraine continues indefinitely and markets tighten further.

“Under the current conditions, I don’t think that Japan has the room to commit to long-term, continuous LNG shipments,” said Michitaka Hattori, a director at the Japan Institute for Russian & NIS Economic Studies.

The surest way to bring prices down is to add more supply. High prices will encourage marginal increases in exports, but it usually takes more than two years to build new facilities for processing gas such as the terminal that Germany wants to build. Of course, LNG demand, which grew 6% in 2021, will most likely continue to grow as China and other countries shift to gas from pollution-spewing coal.

“I think the winter market for gas is going to remain very tight because of Asia’s shift from coal to gas,” said Marco Alverà, CEO of Snam, a large Italian energy company.

Cheniere Energy is moving ahead with a large expansion of its export facility at Corpus Christi, Texas. Qatar also says it is working on adding an enormous slug of LNG in the next five years.

Developers, though, will be wary of whether the current boom in Europe might fade well before the expiration of the new LNG projects, which are generally expected to operate for 20 years or more. And European leaders insist they still view gas as a temporary fix before renewable energy sources like wind, solar and hydrogen take over.

“There is a question mark there about how much new gas will be needed,” Henderson said.

You may like

-

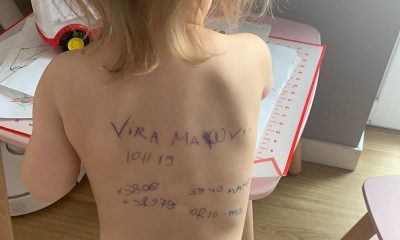

Ukraine war: Scared mum writes family contact info on daughter’s back in case she gets orphaned (Photos).

-

Ukraine War: $4bn scheme launched to cushion Africa.

-

‘These are war crimes’: Ukraine President Zelensky fights back tears during Bucha visit.

-

US may send longer-range anti-aircraft systems, artillery to Ukraine.

-

Ukraine war: Germany says ‘not possible’ to do without Russian gas.

-

‘It’s not a battlefield, it’s a crime scene’ – European leaders react after 410 bodies of civilians allegedly killed by Russian soldiers are found in mass graves in Ukraine (photos).

-

Ukraine war to halve global trade growth, warns WTO.

-

Ukraine War: Joe Biden says Vladimir Putin ‘cannot remain in power’ – (VIDEO).

-

Vladimir Putin’s ‘end date’ for Ukraine war.