International

Scientists warn Brazil’s rainforest is nearing a point of irreversible decline.

Published

2 years agoon

By

Joe Pee

The drive through Sao Paulo state in Brazil is decidedly unremarkable, blocks and blocks of high-rise buildings give way to commuter highways and eventually to gentle rolling hills. It is hardly the scene where one would expect to find the climate’s salvation.

And yet as Luis Guedes Pinto climbed his sky-high perch above a reclaimed swath of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, he explained you don’t have to go to the Arctic or even the Amazon to learn how to nurse Earth’s forests back to health.

“This project doesn’t change a big landscape, but it shows it’s possible to bring back life, to bring back water, to bring back biodiversity, to the center of the state of Sao Paulo,” said Pinto, the CEO at SOS Mata Atlântica, as he pointed down to two square miles of forest restoration.

Deforestation is accelerating in Brazil as Bolsonaro’s first term ends, experts say

Pinto’s organization is a non-profit devoted to rehabilitating the swath of forest on Brazil’s Atlantic coast. The forest itself is home to more than 145 million Brazilians, and — just as the Amazon rainforest has been ravaged by deforestation in the past several years — around three-quarters of it has already been wiped out by urban and infrastructure development and aggressive agribusiness practices.

“We need to plant and replant, but we cannot lose another acre,” Pinto said as he guided CNN through a nursery with more than 50 species of carefully cultivated trees and plants in what was once degraded, drought-prone pasture. “A forest we replant is not going to be the same as a forest we cut down. Some of the forests we’re losing have trees in them that are hundreds of years old.”

These are the seedlings of a forest’s revival. In just 15 years, it has become a thriving eco-lab with a healthy water table, trees, plants and animals. It is a completely different landscape to the pasture land on its borders, where drought-stricken grass overtakes acres of what was previously forest.

Vasco Cotovio/CNN

Vasco Cotovio/CNN

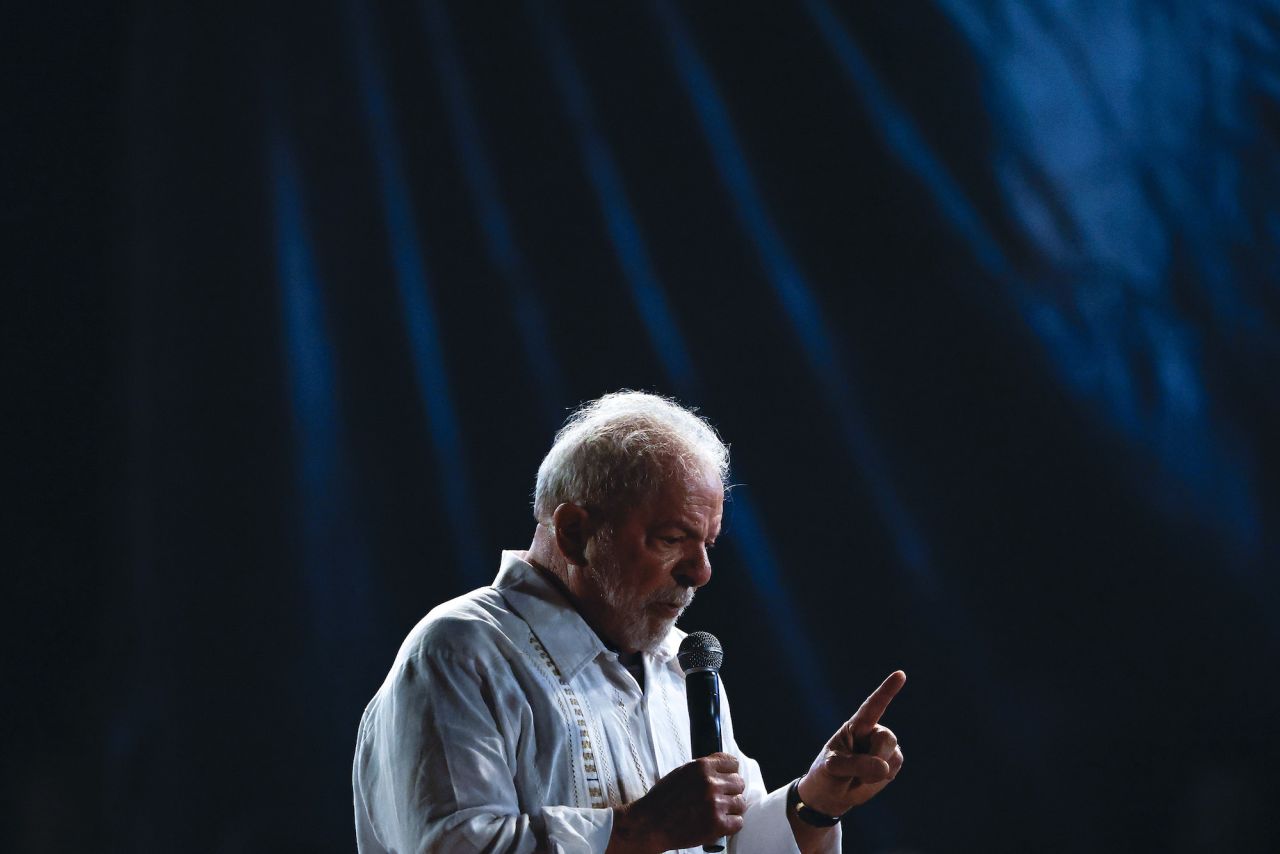

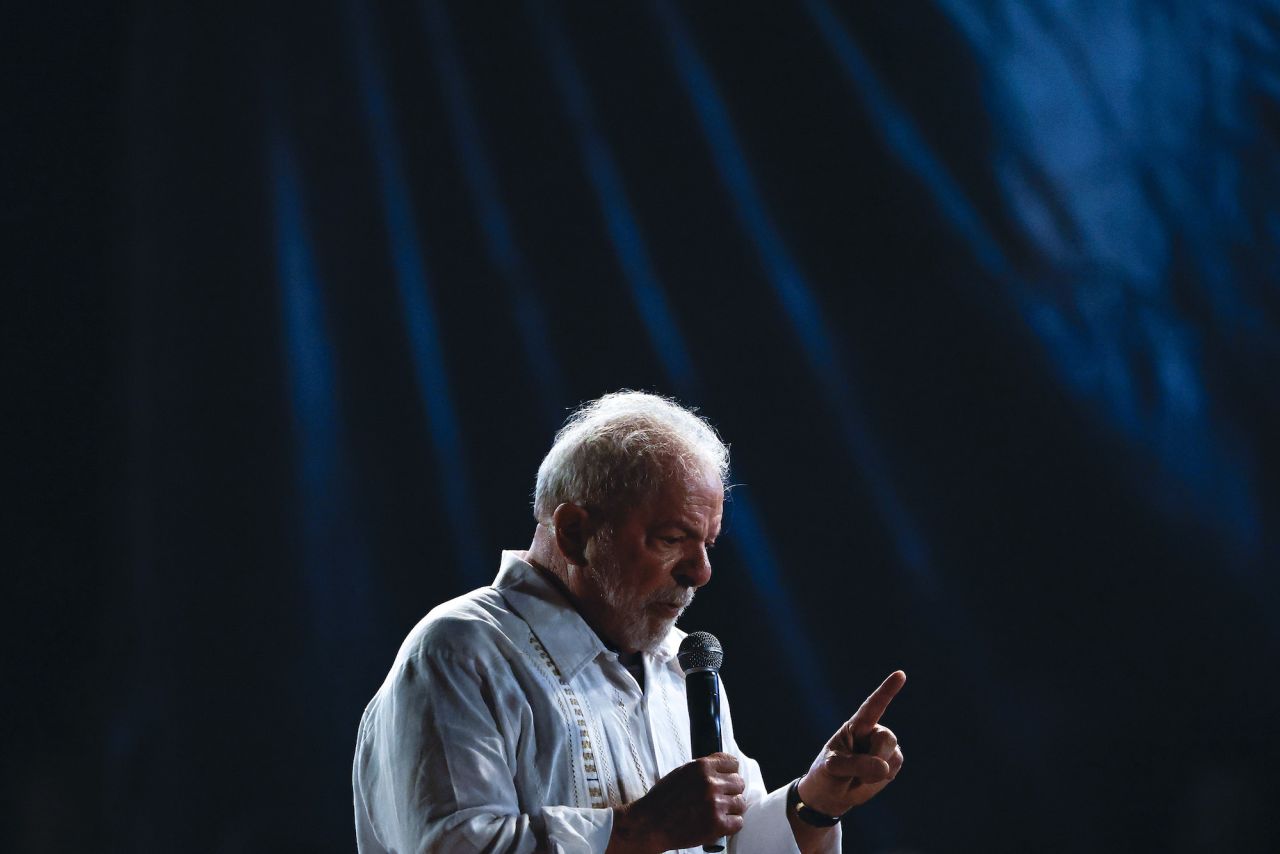

As president-elect Lula Da Silva comes into power, projects like this are now at the crossroads of climate and political history in Brazil, a country that is home to one of the planet’s most significant stores of biodiversity.

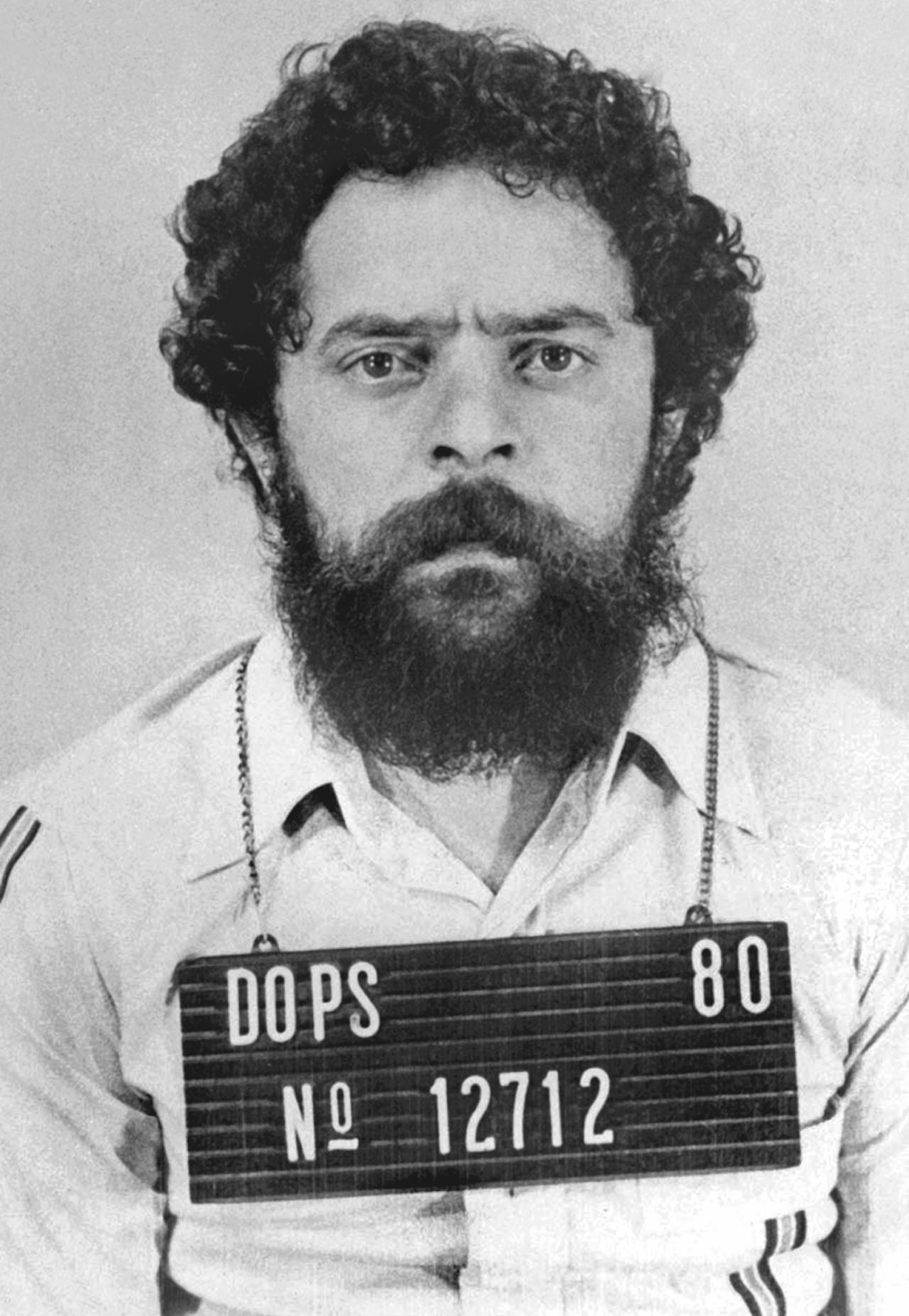

For nearly four years, the government of President Jair Bolsonaro was accused of undoing the environment progress of Lula, who served as president from 2003 through 2010. Data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research show the rate of deforestation under Bolsonaro’s presidency climbed by more than 70% from 2018 to 2021.

Already the Amazon rainforest is emitting more carbon dioxide than it absorbs in some locations — a shift that could have an enormous negative impact on global warming trends. And scientists warn the precious rainforest is nearing a point of irreversible decline and is less capable of recovering from disturbances like drought, logging and wildfires.

Buda Mendes/Getty Images

Lula’s record as former president shows his government was able to cut deforestation rates dramatically by the end of his term in 2010. And his new promise goes even further: to reach zero deforestation in Brazil. This would be substantially more ambitious than his previous government’s goal to eliminate illegal deforestation, not deforestation of all kinds.

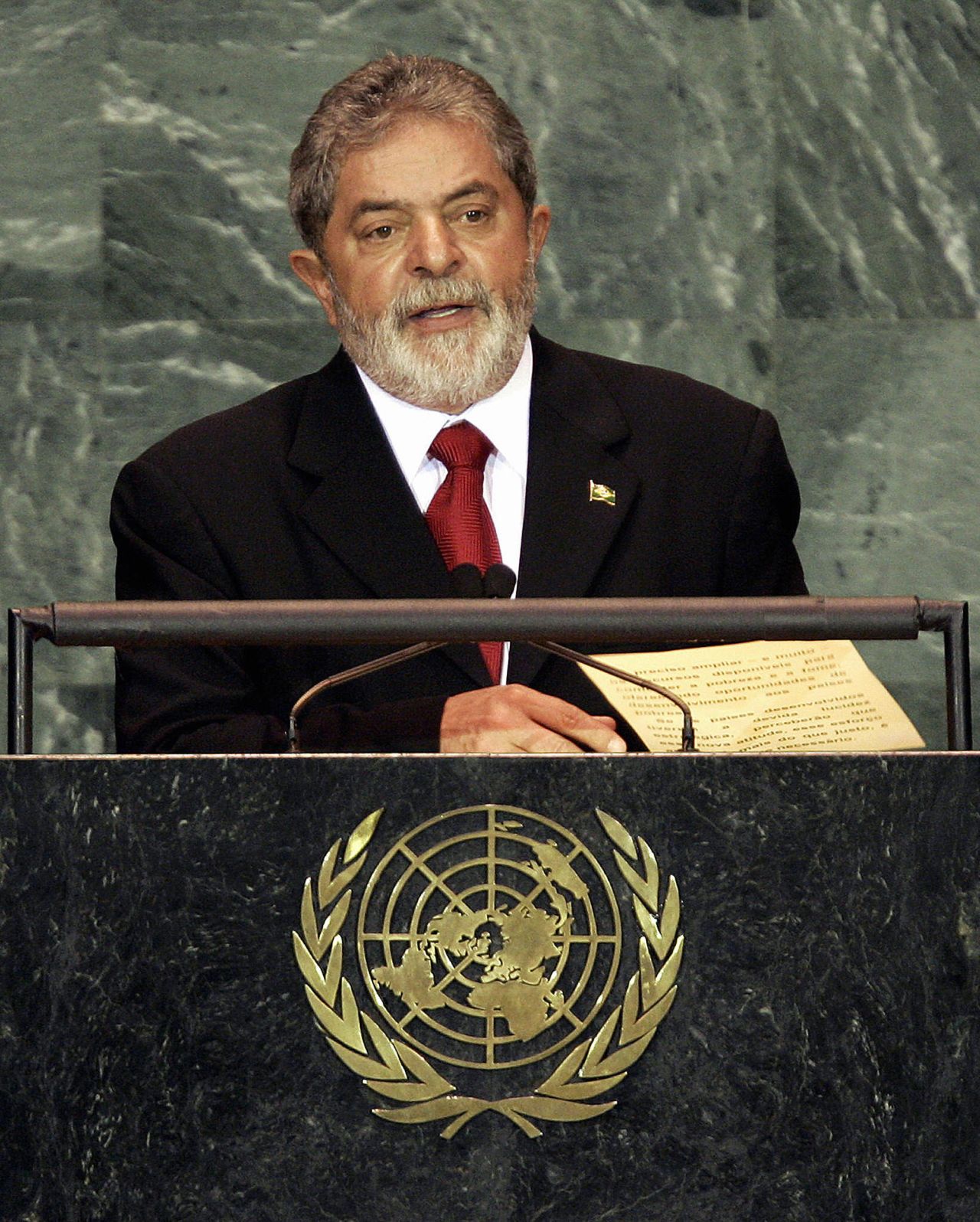

Speaking at the UN’s COP27 climate summit on Wednesday in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, Lula told a jam-packed conference room that “Brazil is back to resume its ties with the world,” and there is “no climate security for the world without a protected Amazon, and we will do whatever it takes to have a different vision in the degradation.”

He also promised to punish those who are responsible for the deforestation in Amazon, and announced a new ministry for indigenous people “so that the indigenous people themselves can present and propose to the government about policies that can derive their survival with dignity and security, peace and sustainability.”

His remarks were met with huge applause that trickled out of the conference room into the hallway, where people who were not able to get into the crowded room, but eager to hear Lula speak on the climate crisis, watched from their phones.

But Bolsonaro allies, who continue to control congress, could make climate action much more difficult over the next four years. One of those allies is Ricardo Salles, Bolsonaro’s former environment minister and now a newly elected lawmaker in Brazil’s conservative-leaning congress.

Vasco Cotovio/CNN

In an interview with CNN, Salles said he and others are willing to work with Lula’s incoming administration on climate goals, but cautioned it should not come at the expense of economic development.

“I was the only guy as minister of environment in the entire history of the ministry who brought these economic questions to the table,” said Salles. During his time as environment minister, the Bolsonaro government often described development and economic activity in the Amazon as vital to longterm sustainability – an approach decried by many environmental activists in the country.

Salles says Brazil will have to work closely now with international allies into order to tap the billions of dollars in climate funds and carbon credits now on offer both by governments and businesses worldwide.

But climate advocates argue neither Brazil nor the planet can afford the kind of compromises now being advocated by Bolsonaro allies.

Vasco Cotovio/CNN

“We don’t need to destroy to develop. We can do that in harmony with nature. And it’s the indigenous peoples who teach that,” Brazilian indigenous leader Txai Suruí told CNN.

Suruí said she is optimistic Lula’s government will make good on promises to act quickly, despite the economic pressure from not only Bolsonaro allies, but millions in the Amazon whose livelihoods depend on its commercial development.

“Because that agenda — of the Amazon, of climate change, of the environment — it’s a global agenda,” she said. “If Lula does not address it, it won’t just be us, indigenous people, that will be knocking on his door, it’ll be the entire world.”

The urgency to commit to those goals is not lost on Pinto who says it’s not just Brazil’s future that is at stake.

“We need to understand as a nation that is key for the planet and that decisions we will make will be important for us but also for others,” he says.